Meanwhile, Gibson President David Berryman opened an Epiphone office in Seoul, appointed Jim Rosenberg as product manager, and set about re-introducing Epiphone to the world as an innovative guitar maker. This was a major turning point for the brand as engineers and luthiers collaborated to re-make the company.

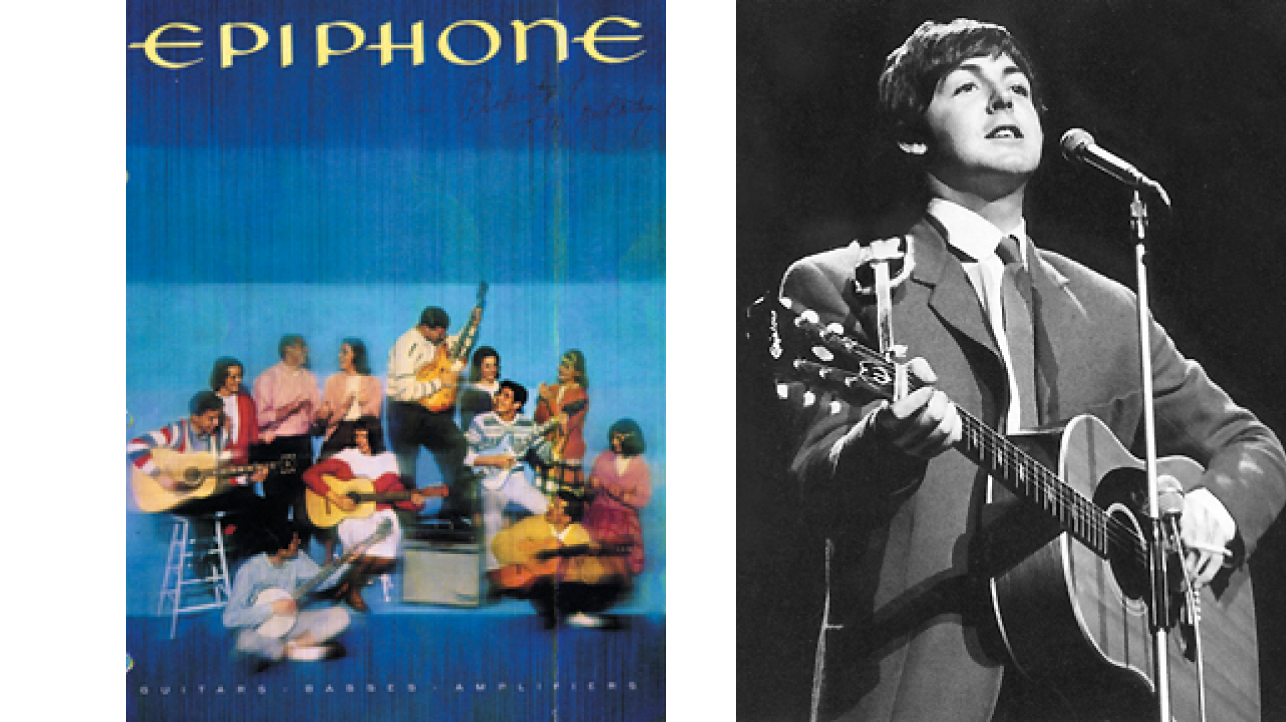

Factory processes were assessed and refined, and Epiphone’s own engineers took a hands-on role in the development of pickups, bridges, toggle switches, and inlays, as well as unique features such as the metal “E” logo and Frequensator tailpiece. Financially and emotionally, everything was invested into these new models, and the marketplace responded. At NAMM 1993, a new range of acoustic and electric instruments debuted to rave reviews and customer response.

1993 also saw Epiphone production return to the USA, albeit in a limited fashion, for a run of Rivieras and Sheratons from Gibson’s Nashville factory and Excellente, Texan, and Frontier models from Montana. The positive reaction prompted Rosenberg to reissue more classic designs, and NAMM 2004 saw the reintroduction of legendary models such as the Casino, Riviera, Sorrento, and Rivoli bass. Soon, a diverse range of stars, from Chet Atkins to Noel Gallagher, were onboard as signature artists – confirmation that Epiphone was a major player once again. In the late 1990s, the John Lennon 1965 and Revolution Casinos reunited Epiphone with one of the greatest artists of all time, underlining the company’s own re-emergence.

In 2000, Epiphone introduced the Elitist range and strengthened its position in the acoustic market with the acquisition of veteran Gibson luthier Mike Voltz. Voltz contributed greatly to Epiphone’s redevelopment, overseeing the reintroduction of the Masterbilt range along with the 2005 reissue of the Paul McCartney 1964 USA Texan. International demand for all things Epiphone was so high that the company opened a new factory in Qingdao in China in 2004, the first time that Epiphone had its own dedicated factory since Gibson acquired the brand in 1957.